-

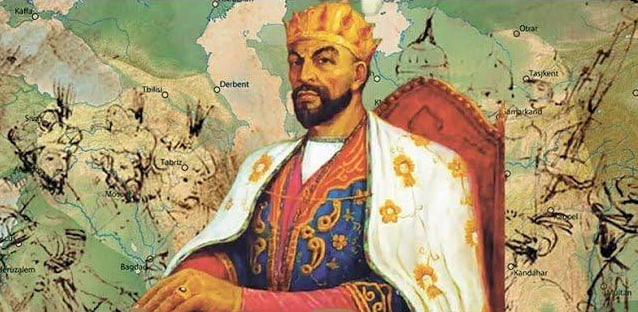

Amir Temur (1336–1405) holds a special place in the history of the peoples of Central Asia as an outstanding statesman and a brilliant military leader.

Remarkable architectural masterpieces were erected during this period: the Juma Mosque, the Gur-e Amir Mausoleum, the Shakhi-Zinda Architectural Ensemble, and the Bibi-Khanum Mosque in Samarkand; the Dorus-Saodat Mausoleum and Ak-Saray Palace in Shakhrisabz; the Chashma-Ayub Mausoleum in Bukhara; and the Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmad Yasawi in Turkestan, among many others. These monuments have withstood the test of time and remain well preserved to this day. Particularly noteworthy are the various types of architectural decoration from the Timurid era, which are represented in the exhibition.

Timur devoted great attention to the development of science and culture. When addressing important matters, he first consulted scholars and specialists in the relevant fields. His court gathered prominent figures in the natural sciences, mathematics, astronomy, literature, history, linguistics, as well as renowned theologians. Among those who served at his court were such distinguished individuals as Mavlono Badriddin Ahmed, Shamsuddin Munshi, Mavlono Nigmatiddin Khorezmi, Khoja Afzal, Mavlono Alauddin Kashi, and others.

It should be noted that Timur had a deep passion for artistic literature, especially poetry. In Samarkand, Herat, Balkh, and other cities of the empire, poets such as Attoi, Sakkoki, and Lutfi created their works—figures who were later praised with great admiration and respect by Alisher Navoi.

For the purpose of establishing diplomatic relations, he sent envoys to various countries and addressed letters to the courts of King Henry III of Castile, Charles VI of France, and Henry IV of England, and he also received ambassadors from Spain, France, England, China, and other nations. He established diplomatic ties with Venice, Byzantium, and Genoa.

From the fifteenth century onward, manuscripts about the period of his rule were created in Europe, which later became important sources for studying the history of that era. Among them are the accounts of the envoy and monk Johann Schiltberger, the merchants Paolo Zane, Beltramo de Mignanelli, and Emmanuel Pilotti, the Spanish ambassador Ruy González de Clavijo, and the captured German soldier Johannes Schiltberger. There are also chronicles about Timur written by Eastern authors such as Ghiyas ad-Din Ali and Arabshah.

In conclusion, it becomes clear why historians refer to this period as the Second Eastern Renaissance.

In 1405, during his campaign to China, Amir Timur died, according to sources and historians, from pneumonia. His tomb is located in Samarkand, in the Gur-Emir Mausoleum.

The exhibition features a panel created by a team of artists led by Alisher Alikulov, along with artists Agankhanyans and Gulmetov, painted in 2002 and dedicated to Amir Timur. It depicts Timur himself on a white horse against the backgound of magnificent architectural structures, the trade route from Asia to Europe, a battle with the last Chinggisid Toktamish, and envoys from Europe and Asia. The panel also includes scenes illustrating the development of science and culture during Timur's reign.

The exhibition features a map of Amir Timur’s 14th-century state, coins of the Timurid dynasty rulers, a hoard of Timurid coins discovered in the Tashkent region, the genealogy of the Timurids, equipment and weaponry of a soldier of Timur’s army, as well as armor and a fragment of a helmet from excavations in Shakhrukhia (Akkurgan, Tashkent region).

An outstanding representative of the Timurid dynasty was Timur’s grandson, Mirzo Ulughbek (full name — Muhammad Taraghay ibn Shakhrukh ibn Timur Ulughbek Guragan). Ulugh Beg’s father, Shakhrukh, was Timur’s younger son and ruled in Khorasan. Ulugh Beg was born on March 22, 1394, in the city of Sultaniya (Iraq).

The reign of Ulugh Beg is rightly called the era of the highest cultural flourishing of Transoxiana. As a result of several military campaigns, in 1413 he annexed Khwarezm to Transoxiana, later Fergana, and then confronted the Mongol Khan of the White Horde, Barak, where Mirzo Ulughbek forces were defeated. This failure forced Ulugh Beg to abandon military campaigns, and unlike his political pursuits, his attention turned to science—particularly astronomy, as his interest in celestial bodies had appeared in early childhood.

Thanks to his lineage, Mirzo Ulughbek had the opportunity from a young age to access the best libraries and observatories of the time. His teacher was the scholar, mathematician, and physicist – Kazizade Rumi. Later, in Samarkand, he began constructing his own observatory. Its construction was completed in 1428. In terms of equipment and scientific achievements, this observatory had no analogues in the world at that time, nor for many years afterward. Outstanding astronomers worked there, who, along with Ulugh Beg himself, made enormous contributions to the development of this science.

The underground part of Mirzo Ulughbek s observatory has been remarkably well preserved to this day a quadrant, displayed in the exhibition as a model and photographs. It was in this observatory that the great Ulugh Beg compiled the Star Catalog — the Guragan Zij, astronomical tables that provided the coordinates of 1,018 stars. The length of the stellar year was also determined here: 365 days, 6 hours, 10 minutes, 8 seconds (with an error of only +58 seconds). Considering the absence of specialized observational equipment, such results testify to Ulugh Beg’s profound knowledge in mathematics, geometry, and astronomy. These tables are considered his main scientific work. Until the 17th century, the accuracy of these tables surpassed all other existing data in this field.

Later, his “Star Tables” were published in various countries: in 1665 in Oxford (by Thomas Hyde), in 1843 in France (by Baillie), and in 1917 in England (by Edward Ball Knobel).

Ulughbek’s statement, “A Muslim man and woman must possess knowledge,” was a call for education and enlightenment, reflecting his desire to make science accessible to both men and women. This call was part of his policy of establishing educational institutions, such as madrasahs in Bukhara and Samarkand, which served as centers of higher learning.

His works have survived to the present day, including: “Zij-i Jadid-i Gurghani” (“The New Astronomical Tables of Gurghan”), “Risala-yi Ulughbek” (“Ulughbek’s Treatise”) on astronomy, “Risala dar Istikhraji Jaibi Yak Daraja” (“On the Calculation of the Sine of One Degree”) on mathematics, and “Tarikh-i Arba Ulus” (“The History of the Four Ulus”), dedicated to the history of Central Asia in the 12th–14th centuries, including the Mongol period.

Alongside his diverse scientific activities, Mirzo Ulughbek founded a library so that its resources and sources could be used not only by himself but also by other scholars and research groups. The library included both his own works and the works of other scientists. In terms of the number of books on astronomy, mathematics, and architecture, the “Ulughbek Library” was unparalleled and was the only one of its kind in the world in the 15th century.

Mirzo Ulughbek, as well as his student, friend, and like-minded scholar Ali Qushchi, whom contemporaries called the “Ptolemy of his time” for his knowledge of mathematics, astronomy, and overall erudition. In his treatise on geometry, Ali Qushchi provided complete definitions of concepts such as point, line, plane, and circle, studied natural sciences, and was a materialist philosopher.

Ulughbek’s domestic policy differed from that of his predecessors. Socially, he sought to improve the conditions of the common people. Land taxes were minimized, which contributed to the growth of the agricultural population’s prosperity. He built baths, schools for ordinary people, and khonaki (lodging houses for travelers and dervishes). By his order, madrasahs (Muslim educational institutions) were constructed in Samarkand, Bukhara, and Gijduvan.

Of particular note is the Samarkand structure in the center of the bazaar square, which marked the beginning of the Registan architectural ensemble. In terms of architecture, artistic design, and durability, these buildings in no way fall short of the majestic constructions of his grandfather, Timur.

The development of science in Mawarannahr faced unprecedented resistance from reactionary forces. They saw Ulughbek as a threat to their political and economic dominance. Ulughbek was declared an “impious ruler,” and unrest and suspicion were spread against him. Relations with his eldest son, Abdullatif, became strained. Surrounded by Ulughbek’s enemies, his son took the vile path of removing his father from his way once and for all. A treacherous plan to assassinate Ulughbek was devised. With Abdullatif’s consent, a group of religious leaders and judges issued a death sentence, and in October 1449, the great scholar was treacherously killed.

After Ulughbek’s tragic death, many scholars and students dispersed. Ali Qushji also left the country, but abroad he published the results of his many years of astronomical observations — “The New Gurghani Tables of Celestial Bodies.”

The exhibition features portraits of Mirzo Ulughbek and Ali Qushji, engravings from the book of the Polish scholar Jan Heweliusz, Astronomy Messenger (18th century), and a copy from the Stanford University collection — the 1665 Latin edition by Thomas Hyde, which includes Ulughbek’s complete star catalog. Displayed are images of European engravings showing Ulughbek among the world’s astronomers, examples of writing instruments, and portable astronomical tools — astrolabes and other devices widely used by Muslim astronomers up to the 18th century.

Ulughbek’s reign is rightly regarded as the era of the highest cultural flourishing of Mawarannahr.

Babur — full name Zahiruddin Muhammad Babur — was born on February 14, 1483, in the city of Andijan (northeastern part of present-day Uzbekistan). He was the eldest son of Umar Sheikh Mirza, ruler of the Fergana Valley, who was the son of Abu Sa’id Mirza and the grandson of Miranshah, himself a son of Timur. Babur faced many hardships in his life, and to overcome them, he had to demonstrate courage, self-confidence, and resilience on the battlefield and in other dangers.

The early stage of his life was closely connected with military campaigns and battles. During this period, his main task was to unite the regions of a once vast empire, which had become fragmented after the death of his ancestor, Timur.

In 1497, Babur managed to establish his authority in Samarkand, the former capital of Timur’s empire. However, in 1501, he received news of the advancing forces of Sheybanikhan into Mawarannahr. There was an unsuccessful battle for Samarkand, in which Sheybanikhan emerged victorious. Then, through a sudden strike, Babur managed to seize Samarkand, and fortune began to favor him.

However, Sheybanikhan, an experienced steppe warrior with a large army, was patient and launched a systematic, long-term campaign. During this, Babur lost his best generals and brave soldiers. Moreover, part of his army, composed of Mongol soldiers, betrayed him, and the ruler of Herat, Husayn Bayqara (also a Timurid), refused to provide support. Sheybanikhan blocked all roads to prevent supplies from reaching the city. The army suffered from hunger, and there was no fodder for the horses. Babur was forced to surrender and conclude a peace agreement to exit the city safely.

After enduring brief but harsh battles, trials, and humiliations — without troops, weapons, money, allies, or close confidants — he returned to his native Andijan. Yet his authority there was also fragile. Taking his mother, family, and some followers, nukers and servants, he moved to Afghanistan and established himself in Kabul.

But Babur’s ambitions drew him further — toward India. He aimed to create a wealthy and powerful state. In 1526, he conquered India and founded the mighty state known in history as the Mughal Empire, which lasted for nearly 300 years.

Babur was not only a politician, statesman, and military leader, but also a talented poet. His lyrical quatrains, known in the East as rubai, continue to captivate many to this day.

He is also known worldwide for his diary, “Babur-nama” (“The Memoirs of Babur”), which he kept throughout his life. It describes his own life, historical events, countries and their geographical locations, the animal and plant world, as well as the customs and rituals of different peoples.

Civil strife, feudal reaction, the fanaticism of some misguided religious movements that strayed from the true path of Islam, and many other factors led to the cultural decline of Mawarannahr. The ruler and scholar Ulughbek was killed, his observatory destroyed, madrasahs — centers of education — were closed, and educators, scholars, poets, and artists fled to the realm of thinkers and free thought, Herat — one of the most brilliant cultural centers of the East in the 15th–16th centuries, closely associated with the wise vizier and great poet Alisher Navoi.

Alisher Navoi was born in Herat in 1440. He was a wealthy and influential statesman and a close friend of the ruler Sultan Husayn Bayqara, a Timurid by origin.

He used his position and resources for extensive construction activities. On his initiative and at his expense, more than 300 buildings were constructed: palaces, mosques, mausoleums, as well as public facilities such as baths, hospitals, pools, and bridges. Navoi was a patron of many outstanding musicians, including Ustad Kul Muhammad, Sheikh Nayi, and Husayn Udi, and of artists such as Behzad and Shah Muzaffar. The great Eastern poet Abdurrahman Jami was also a close friend of Navoi.

Alisher Navoi’s name is associated with the highest flowering of Uzbek poetry. He demonstrated the beauty and rich poetic potential of the Uzbek language, which became widely used in literature, science, and art, as well as in everyday life. His immortal works, including “Khamsa,” “Chor Divan,” “Majalis un-Nafais”, and others, are imbued with humanism, glorification of labor, praise, and calls for goodness and the eradication of evil: “...to establish justice everywhere, to free peoples from oppression!” He exalted peace, stating: “It is sinful to stand aside when you can prevent war!”

The beauty of Alisher Navoi’s poetry, along with the humanism and democratic spirit of his works, transformed the poet into a wise mentor and spiritual guide for the broader masses. His works spread widely across the East through storytellers and folk poets, becoming a school of nobility, justice, ethics, and morality.

Kamoliddin Behzad was an outstanding miniature painter of the second half of the 15th century and the founder of the Herat school of miniature art.

According to historical accounts, Behzad was orphaned at an early age. He was raised by the famous calligrapher and artist Mirek Nakkash Khorasani, who held a high position at the court of Sultan Husayn Bayqara as kitabdar — the chief librarian.

The development of Behzad’s personality and worldview was greatly influenced by Alisher Navoi — vizier, poet, and humanist — who created the unique creative atmosphere that characterized the cultural life of Herat during the rule of Sultan Husayn Bayqara. Historians believe that Navoi was the direct patron of the young talent. The historian Khondamir states that by the age of twenty-three, Behzad had already become the leading artist of the Herat workshop.

In the 1480s, several manuscripts produced in the library of Sultan Husayn Bayqara are believed by scholars to bear the artistic work of Kamoliddin Behzad. In these manuscripts, Behzad reveals himself as a master of landscape, of battle scenes, and of depicting human figures with their individual characteristics. Many artistic innovations are attributed to him. His compositions are marked by a special sense of balance and harmony. Before Behzad, it is nearly impossible to find another Eastern artist who arranged human figures and other compositional elements with such impeccable taste and sense of proportion.

He possessed exceptional mastery of line, which gave his figures a distinctive sense of movement. Moreover, in his depictions of people, Behzad strove for portrait-like resemblance, and for this reason, researchers often identify recurring individuals in his miniatures — for instance, Sultan Husayn Bayqara himself and others. He is also credited as one of the first to portray different skin tones, reflecting real human diversity. Behzad enjoyed incorporating scenes from everyday life into his miniatures.

In addition to his own artistic work, Behzad trained an entire generation of painters, including Qasim Ali and Mahmud Muzahhib. He also created numerous illustrations for literary works, as well as portraits, genre scenes, and battle compositions.

Behzad’s world-famous works include scenes from the poems “Khamsa” (“Five Poems”) by Alisher Navoi, “Layli and Majnun”; scenes from the chronicle “Zafarnama”; the portrait of Husayn Bayqara; the portrait of Shaybani Khan; “Construction of a Mosque”; “The Seven Sages”; “The Bathhouse”; “The Dance of the Dervishes”; the portrait of the poet Hatifi; “The Wedding of Mushtari”; “The Old Man and the Youth”; “The Battle of Timur with the Egyptian Sultan”, and many others. These works are valued both as artistic masterpieces of high aesthetic level and as important historical sources reflecting the events of that era.